An Unexpected Encounter

Gravel flies as a Jeep skids to a halt in front of us. “What are you doing here?” the driver shouts as he jumps out. Joseph Wolf and I are both startled, and I am definitely puzzled. I had secured permission from the property owner to visit the site of old Brazil Station, or so I thought.

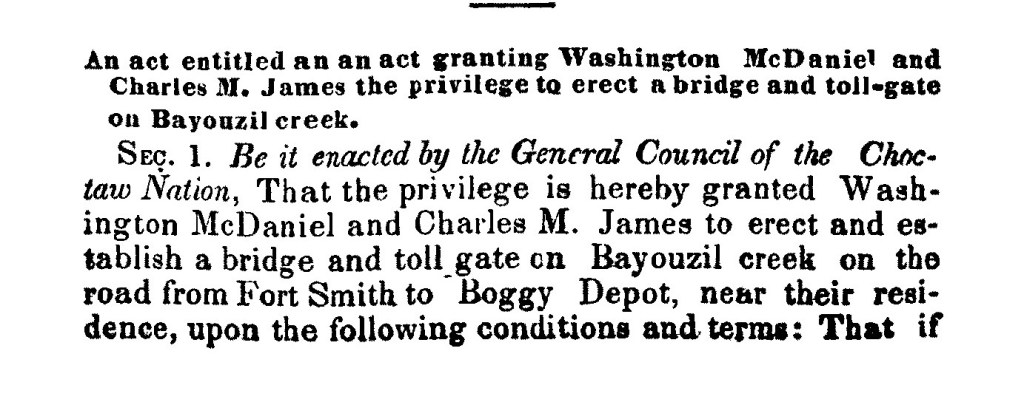

Located along the Butterfield Overland Mail Road about fourteen miles southwest of Skullyville in the Choctaw Nation, Brazil Station was founded as a trading post after the Civil War by David Robert Welch, an Irishman who came to Indian Territory via Alabama. Although the site was not an official Butterfield stand, the Choctaw legislature awarded Washington McDaniel and Charles M. James the concession for a toll bridge across nearby Brazil Creek in October 1858, concurrent with the initiation of the Overland Mail.

The location also served as a local mail stop.[i] Butterfield historians Roscoe and Margaret Conkling and Muriel Wright spent considerable time here on their retracing adventures. Following suit, Joe and I have been examining the ruins, a cemetery and a road trace. Oblivious to the idea that we could be trespassing, we showed up on a game camera and the property owner alerted a friend, who is the man accosting us now. I explain that we have the owner’s permission to be here, making sure he knows that Joe is with the Choctaw Nation’s Office of Historic Preservation in hopes that it will lend us some credibility . . . and safety.

“Who’s the property owner?” he demands, maintaining his sternness but becoming somewhat less threatening. I tell him her name and he informs me she sold the property to his friend some time ago. At first I am shocked and then feel utterly betrayed. I was in contact with her that very morning, even at the moment Joe and I parked at the gate. I knew she was eccentric, but never dreamed she would intentionally deceive and endanger us. At our first meeting, she arrived in a pickup studded with auxiliary lights for catching poachers, making threats about what she would do to trespassers and stating not so subtly how suitable old wells are for hiding bodies. From that moment on I knew not to cross her and scrupulously obtained her permission for each subsequent visit, but now I see that my ginger handling of the relationship was for naught. Thankfully, the Jeep driver softens up and gives me the name and phone number of the current owner for future use. And, on the bright side, I have now made four visits to Brazil Station without getting shot. Certainly, other early travelers along the old stagecoach road did not feel entirely safe during their traverse of Indian Territory so I suppose it could be considered a meaningful moment of empathy.

As I have explored the remnants of the Butterfield Overland Mail stagecoach road in Oklahoma, my experience with property owners has been consistently positive other than this, and even this one seemed friendly at first. Trespassing is taken seriously here, and with few exceptions, I have been scrupulous about contacting the owner and asking permission before visiting a site on private property.

The Path of the Old Road

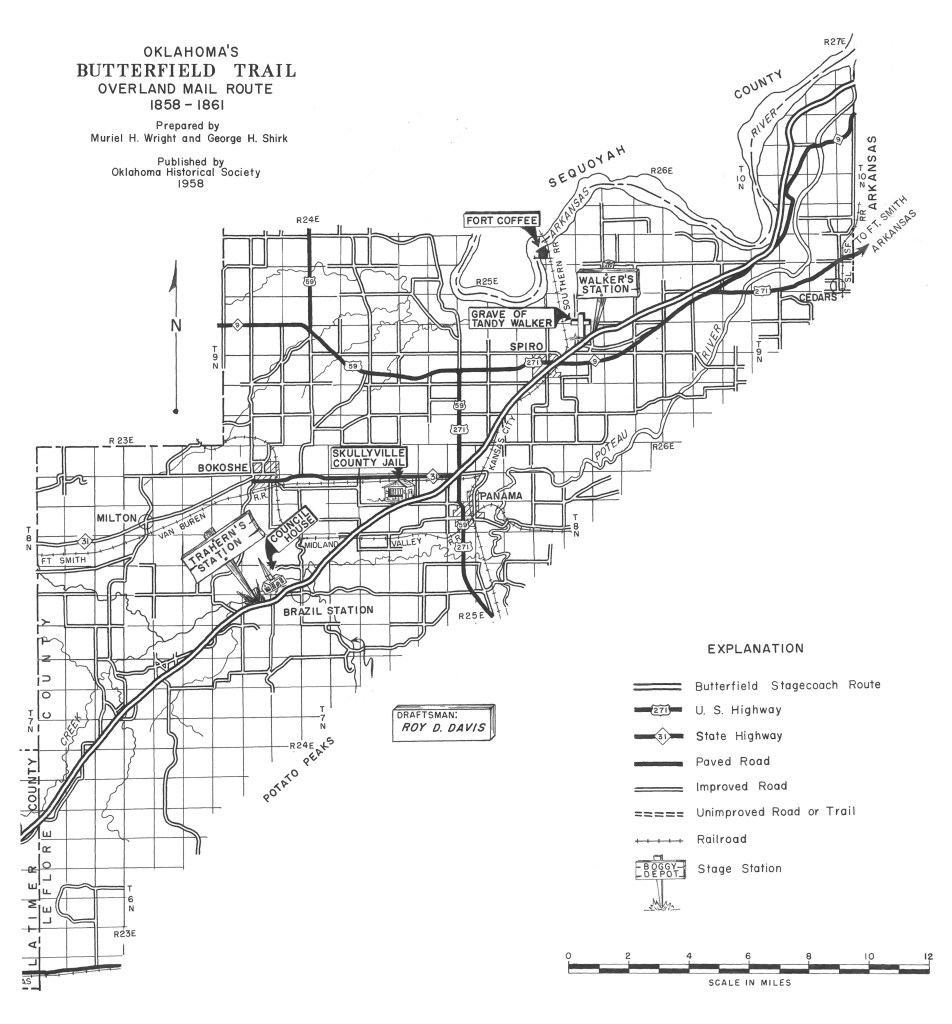

After leaving Walker’s Station, the easternmost Butterfield station in Indian Territory fifteen miles from Fort Smith, the Butterfield Overland Mail stagecoach road passed the present town of Spiro to the south, running southwest toward the Coal Creek crossing. U.S. Highway 271 is close to the line of the old road over part of this distance. About two miles west of Spiro, the road branched into three: the left fork the Overland Mail route, the right fork the road to Edwards Trading Post on Little River in the Creek Nation, and the middle fork Randolph Marcy’s California wagon road.[ii] Near the Coal Creek crossing, the mail road curved sharply west and then southwest again, passing to the south of the Skullyville County Jail, which still sits along Rock Jail Road west of Panama, Oklahoma. On private property but easily viewed from the road, the jail is a one-story sandstone building with walls two feet thick and an iron-barred door and window.

Although it did not exist contemporaneously with the Overland Mail’s use of the route, the structure is important as the only surviving building connected with the Skullyville County government of the Choctaw Nation. Originally a courthouse and execution tree also comprised the government complex, built between 1888 and 1895.[iii] The Skullyville County courthouse, which was located north of the jail, burned sometime before 1937.[iv]

From the jail, the mail road continued southwest across Buck Creek, where a mail station was located on a later stage route. It then crossed Brazil Creek, a tributary of the Poteau, and what is known today as Mack Watson Creek. About a quarter of a mile southwest of this last crossing is the site of Brazil Station.

A French Name

But where did the name “Brazil” come from? When I first began to explore the Indian Territory segment of the Butterfield Overland Mail stagecoach line and talked with the locals in LeFlore and Latimer Counties, I noticed “Brazil” was not pronounced the way I expected, i.e. like the country of Brazil in South America, with the emphasis on the second syllable. Instead, in the first syllable the “a” was flattened and drawn out, and the second syllable pronounced like “zeal.” I soon discovered this reflected an alternate spelling, “Brazeale.” Then, I found the creek referred to as “Bayouzil” in historical documents, a discovery which led to its French origins.

Long before the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, French fur trappers and traders of the 1700s hunted and camped along the streams of the Arkansas and Red River valleys in what is now Oklahoma. The names they gave the rivers and mountains reflected the features of the terrain, unusual occurrences, or the routines of daily life, leaving an enduring legacy. Ascending the Arkansas River west of the Oklahoma border, the first stream of any size west is the Poteau, the French word for “post.” The Verdigris River, from the French words “vert” for green and “gris” for gray, evokes the greenish gray color of rocks in the stream. Muriel Wright’s 1929 article in The Chronicles of Oklahoma explores the subject in more detail, mentioning familiar southeastern Oklahoma names like Vian, Sallisaw, Sans Bois and Fourche Maline.[v]

Less obviously French at first was Brazil, but reversing its linguistic corruption made it clear: Brazil, Brazeale, Bayouzil, and on an 1834 map, Bayou Zeal.[vi]

Then, on an 1844 map, I found it labeled “Bayou aux Iles.” “Bayou to the islands.” Perhaps this was its original French name. Why it would be so named remains a mystery.

Back on the Road

Fences through which county roads do not extend now obstruct the path of the old stagecoach road between the jail and Brazil, but a detour over Buck Creek Mountain on Blue Goose Road affords a scenic crossing of Brazil Creek, until recently on a picturesque 1941 Pony Truss bridge, now out of service but still visible off the main road.[vii]

It was replaced with a bridge of concrete and greater safety but certainly less charm. South of the bridge, an obscure lane running east accesses the Brazil Cemetery and ruins of Brazil School.

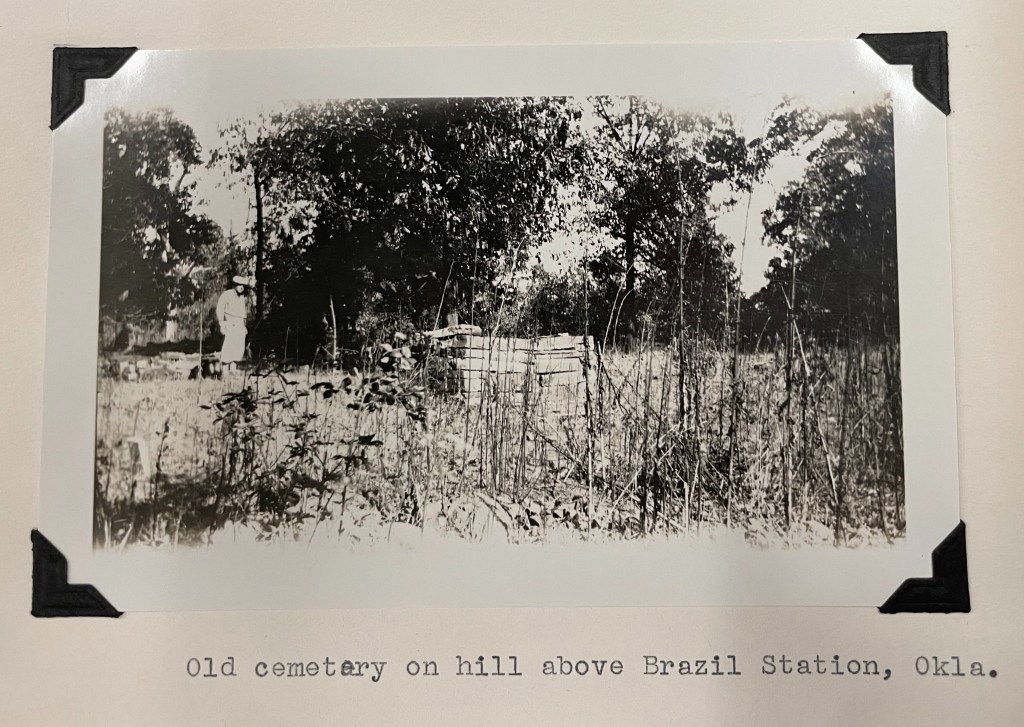

The cemetery is still in use, with recent graves near the road and countless old resting places spreading into the woods, their uninscribed stones scattered among the brambles.

North of the graveyard, a pile of rubble that once was Brazil School hides in the trees, its clearly defined foundation enveloping the stones of the collapsed walls. About the school the Conklings wrote, “After driving all morning without meeting anyone on the road, we felt that we were in a deserted countryside. But when we arrived at Brazil School, there were perhaps thirty children out for recess with the teacher directing their play. All looked modern enough and quite happy even though their school yard was a continuation of the cemetery. Not even a fence line to protect the early graves.”[viii] By 1958 the school was abandoned.

In spite of the fact that Brazil was not an official Butterfield stop, much was written about it in in 1930 and 1958. During their visit in November 1930, the Conklings met Robert Anderson (R.A.) Welch, son of D.R. Welch. At the time, the Conklings believed Brazil Station to be a Butterfield station, as did Welch.

North of the cemetery, a locked gate now blocks access to Brazil Station. This was not the case in 1930, and the Conklings drove past the cemetery and school right up to the D.R. Welch house, near the site of the stage station. They were told the house was built in 1868.

Welch also owned land in the Arkansas River bottom at Geary Lane, later renamed Braden. “The only way through this bottom land was by Geary Lane and as father had control of the land, he made this a toll lane,” said R.A. Welch. “However, this toll fare was only charged for the passage of people who were not citizens of the Territory and all the Choctaw Indians were allowed to go through free of charge.” The younger Welch, born in 1877 to D.R. and his third wife, Phoebe, dated the Brazil settlement’s origins to 1876, contradicting the 1868 date reported to the Conklings.[ix] In an 1885 newspaper article, however, a current resident of Brazil Station wrote that Welch established his trading post in 1872, effectively beginning the Brazil settlement then.[x] The correct date is difficult to determine, but a mention of stopping at “Daniels Station” for rest and forage in April of 1861 by William Woods Averell suggests there was a settlement here prior to the Civil War. During his short stop, Averell may have misinterpreted “McDaniel,” one of the partners who built the Brazil Creek bridge, as “Daniel.” (Source: Ten Years in the Saddle, The Memoir of William Woods Averell, 1851-1862, p. 259.) For more on Averell’s journey, see https://gateway.okhistory.org/ark:/67531/metadc2123780/

A post office named Brazil Station was established on April 11, 1879, with Phoebe Welch as its first postmaster. She was the fifth female postmaster in the Indian Territory, at a time after the Civil War when across the United States more women were being appointed to the role.[xi] When the post office name was changed to Brazil in 1895, the postmaster was Phoebe Reagan, who, we may surmise, remarried after D.R.’s death in 1892. The Brazil post office was discontinued in 1913.[xii]

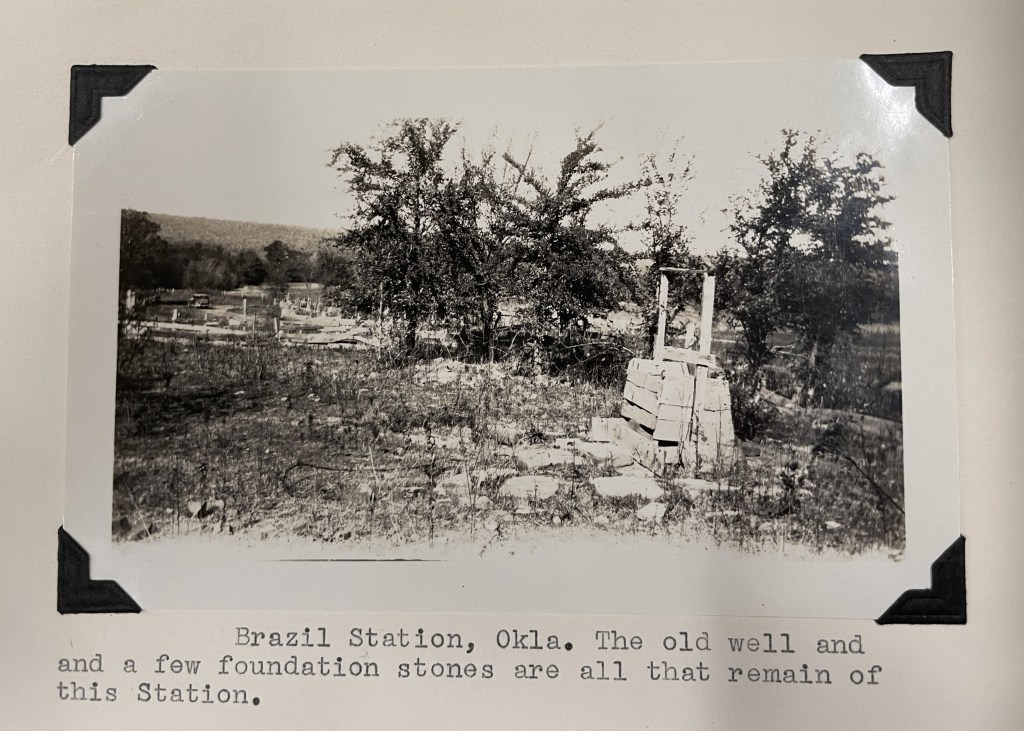

The Conklings and the Centennial Committee, led by Muriel Wright and sent out by the Oklahoma Historical Society in 1958 to identify Butterfield station locations, found the ruins of the Brazil stage station northwest of the Welch house, near the creek. The Conklings wrote, “The ruins of the old stage house are about half a mile West of the Welch house. Across the road from the Welch house are ruins of a blacksmith shop and warehouse.”

The station ruins are no longer evident, but the Welch family grave plot near the house, an old well and a row of bois d’arc trees mark the site, changed little since 1958.[xiii]

A lane east of the ruins of the house leads to the locked gate blocking entry from the south, the access point for both the Conklings and the Centennial Committee. Black locust trees also observed in 1958 still flourish, their long thorns creating a hazard for the distracted walker, especially near the small cemetery.

An ornate wrought-iron fence topped with the fleur de lis surrounds the picturesque Welch graveyard. D.R. Welch’s tombstone is in the southeast corner, broken off at the base but otherwise in good condition. The small plot contains several other markers including that of D.R. Welch’s second wife, Lucinda.

Before my site visit with Joe Wolf, I came alone and walked the mail road’s path from Brazil Station northeast to the Brazil Creek crossing. From the Brazil settlement, the trail quickly enters a deep rut flanked by large trees, the width of a narrow road. It was difficult to walk in the depression, where small trees and briers grow thickly. I crossed Mack Watson Creek, the water shallow and the rocks slippery. Continuing through a pasture, I saw an old ruin on a slight rise. Its roof had collapsed but a stone-lined well remained intact, sheltering a snake in its cool interior.

On a well-defined and recently used two-track, I soon arrived at Brazil Creek. A likely crossing site was evident where the creek bank is cut down on the east and a path gradually ascends from the creek on the west. The location is consistent with the crossing on a historic map, and a modern aerial view shows a road trace continuing northeast on the east side of the creek.

Returning from the crossing, the change in perspective made the deep swale of the old road more distinct. With increased resolve to push through the undergrowth, I walked most of the way back to Brazil Station in the trace, about a mile, detouring occasionally for incessant tangles of briers.[xiv]

Later, as I explore the area with Joe before our encounter with the Jeep driver, a cow path beckons us around a pond southwest of the house and well. Soon we enter a depression lined with massive bois d’arcs. The swale ends at the fence bordering the county road, where the stagecoach road continues toward Trahern’s Station, the second official stop on Butterfield’s Indian Territory itinerary.

For more adventures on the Indian Territory segment of the Butterfield stagecoach road, grab a copy of my book, Finding the Butterfield: A Journey Through Time in Indian Territory, at https://a.co/2BE4p7R. Also see https://susandragoo.com/butterfield-oklahoma/ for more resources.

[i] Lula Neighbors. January 13, 1938. Indian-Pioneer Papers.

[ii] Wright, “Historic Places,” 802, n.5.

[iii] Dianne Everman. U.S. Department of Interior. National Park Service. National Register of Historic Places Inventory., Skullyville County Jail, Choctaw Nation,80004286. April 21, 1980, 2-3.

[iv] Izora James. May 27, 1937. Indian-Pioneer Papers.

[v] Wright, Muriel H. (Muriel Hazel), 1889-1975. Some Geographic Names of French Origin in Oklahoma, article, Summer 1929; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. (https://gateway.okhistory.org/ark:/67531/metadc2191709/: accessed December 16, 2025), The Gateway to Oklahoma History, https://gateway.okhistory.org; crediting Oklahoma Historical Society.

[vi] A map of the Indian Territory taken by A. Hitchcock for the A. B. C. F. M. https://5143.sydneyplus.com/archive/final/portal.aspx?lang=en-US

[vii] As of February, 2022, this picturesque bridge had been replaced.

[viii] Roscoe Conkling Papers. Box 9 Stage Photos, Folder 46 Oklahoma Research – Manuscript Material. Diary Pages, M.B.C., Fall, 1930.

[ix] Robert Anderson Welch. June 18, 1937. Indian-Pioneer Papers.

[x] Bob Srout. “Letter from Brazil.” The Indian Champion, Atoka, I.T. March 7, 1885, 4.

[xi] “Women Postmasters,” AboutUSPS.com. 3.

[xii] George H. Shirk. “First Post Offices Within the Boundaries of Oklahoma.” Chronicles of Oklahoma 26, no. 2 (Summer 1948): 190.

[xiii] Wright, “Historic Places,” 807.

[xiv] “Brazil Creek Bridge,” bridgehunter.com.

Such an interesting article! Thank you for your research and field work: Tenacity AND courage. How crazy interesting the No Trespassing encounter with Jeep man. Yikes! I so enjoy your book and continuing finds, stories and history of the Butterfield Overland Mail route and locations.