A Mystery Revealed

By Susan Dragoo

It’s been a mystery for many years . . . who was the “Fisher” of Fisher’s Station, the eleventh (counting east to west) in a chain of twelve official relay stations on the Indian Territory segment of the Butterfield Overland Mail stagecoach road? That mystery may now be solved, thanks to an item in a 1924 edition of a Durant, Oklahoma, newspaper, and other evidence which leads to the conclusion that the likely operator of Fisher’s Station was David Osborn Fisher, a Choctaw citizen who was married to a Chickasaw woman and was also adopted into the Chickasaw tribe.

The Butterfield Overland Mail in Indian Territory

The Butterfield Overland Mail operated from 1858 to 1861, extending from St. Louis, Missouri, and Memphis, Tennessee, to San Francisco, California. Nearly two hundred miles of the 2,800-mile trail ran through the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations in Indian Territory. Located about four miles west of present-day Durant in Bryan County, Fisher’s was the last station in the Choctaw Nation; the stagecoach road entered the Chickasaw Nation about three hundred yards west of the stage stand.

After the demise of the Butterfield line and following the Civil War, the stage stand was known as Carriage Point, possibly because an old carriage broke down nearby during the War and was left to the ravages of time. In 1869, Calvin Colbert bought the stage stand and it became an overnight stop for stagecoach travelers.

Near Fisher’s/Carriage Point the road forked, one branch running south on the Butterfield trail toward Colbert’s Ferry and Sherman, Texas; the other going at a more southwesterly angle, entering Texas at Preston Bend, now under the waters of Lake Texoma. An 1872 newspaper advertisement for the Red River ferry at Preston Bend advises taking “all right hand roads” from Carriage Point to get there.

While the name of the station has long been known via publication of Overland Mail itineraries, the identity of the Fisher’s station keeper has remained a mystery since historians began studying the Butterfield trail. In Indian Territory, most station operators were known to be citizens of the Choctaw Nation, or in one case the Chickasaw Nation. The origins of three station keepers have, however, eluded researchers: Waddell’s, Holloway’s, and Fisher’s.

Muriel Wright’s Theory

Oklahoma historian Muriel Wright invested considerable energy into the question of who ran Fisher’s Station. Correspondence between her and Butterfield scholar Roscoe Conkling in 1935 indicates Wright believed Fisher’s was connected to Fisher Durant, a family member of Dixon Durant, a Choctaw for whom the town of Durant was named. In trying to determine the identity of the station keeper, Wright first considered the Choctaw Fisher family – Silas Fisher, Osborn Fisher, et al. But she concluded that since Silas Fisher had remained in the lower Red River country after the removal and Osborn Fisher ranched and operated a store near Daisy in northeast Atoka County and then settled in Tishomingo, this would be unlikely.

Instead, she noted that the earliest site of the city of Durant was actually made by Fisher Durant, and was known in early days as “Fisher’s Place.” She postulated that the Butterfield road had actually come through Durant, and that Fisher’s Place had been Fisher’s Station. Conkling doubted this conclusion, first pointing out that the Fisher Durant location did not fit into the Butterfield table of distances and the route would have required “a rather rank bend to the east and then southwest again,” a deviation that the road builders would have avoided. “I have investigated the route from Nail’s to Carriage Point and from there to Colbert’s in the field with some of the oldest men in the region and if there was any other road between these points followed by the Overland Mail, these men had never heard of it,” wrote Conkling.

Roscoe Conkling’s Theory

But, Conkling conceded, this did not mean that the station could not have been named for Fisher Durant. He could have been employed by the Overland Mail Company as a station keeper and the station named for him even if his home was near the present location of Durant, but it would seem that some reference to this would have been handed down to his descendants. More likely, wrote Conkling, Fisher was among the more than two hundred Butterfield employees from New York brought west to work on the Overland Mail and placed in charge of stations during the first year of operations. “I was told by the then oldest living employee of the old Wells-Fargo Company, who died some years ago in Utica, that Mr. Butterfield transported more than two hundred of his old employees in New York to the western field to work on the Overland. Many of these were placed in charge of stations during the first year of operations,” Conkling wrote. Few of these remained long, but long enough to have their names identified with the stations along the route, and “for that reason no record can be found to prove their identity,” he added. Conkling included Holloway and Waddell among these.

Wright stuck to her guns, however, asserting it would be too much of a coincidence if Fisher Durant, “the most prominent Choctaw citizen in his locality” had nothing to do with Fisher’s Station, in spite of the fact that his known dwelling was in Durant, four miles east of the stage stand. “He could have owned an extra ranch cabin or erected one specially for a stand on the stage line road west of his home place,” she explained. Wright concluded, “And now I feel almost certain, it must have been that of Fisher Durant.”

It appears that, in the end, Wright and Conkling agreed to disagree. Roscoe and Margaret Conkling wrote in their 1947 tome on the Butterfield, “Because the station ceased to be known as Fisher’s after the Company abandoned the route in 1861, and the old name of Carriage Point restored, it has been suggested that Fisher may have been in the Company employ and temporarily installed there.” Wright later wrote in an appendix to her 1957 article, “The Butterfield Overland Mail One Hundred Years Ago,” that Fisher was a member of a well-known Choctaw family. And in the 1958 Centennial Committee Report, she simply quotes Conkling’s conclusion.

A Different Conclusion

Further research suggests a different conclusion. It seems Wright probably dismissed too quickly the Silas Fisher/Osborn Fisher family as a possibility. In 1924, the Durant Daily Democrat reported a talk given by Jessie M. Hatchett, grand-daughter of Calvin Colbert, who operated the Carriage Point stage stand beginning around 1869. Hatchett stated, “The place was first settled by the Rider family, afterwards owned by the Fishers of Tishomingo, from whom it was purchased by my mother’s father.”

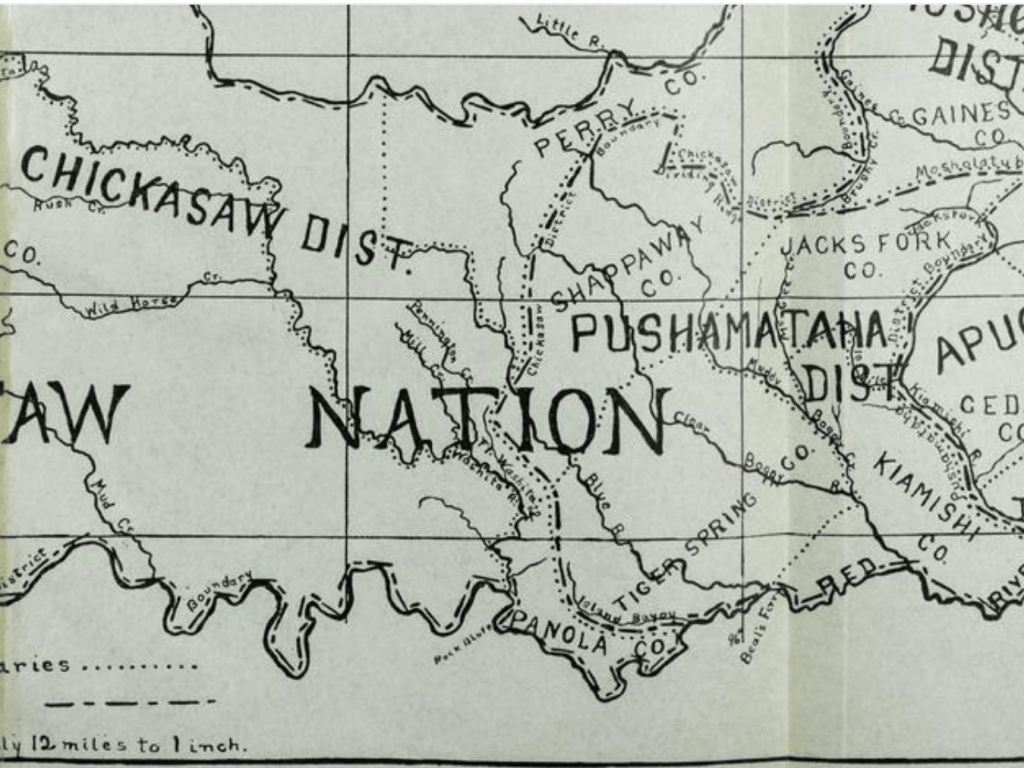

Given that Silas Fisher died in 1849, Osborn Fisher is the more likely candidate. David Osborn Fisher was born in 1825 in Mississippi and moved to Indian Territory with the Choctaws in 1832. In 1837 he relocated to Fort Washita, later establishing a large farm on Red River in Panola County in the Chickasaw Nation. The 1860 federal census (slave schedule) finds him in Blue County (formerly Tiger Spring County) in the Choctaw Nation, where Fisher’s Station was located. There, Fisher enslaved 24 people.

Note (see map below) that Panola County in the Chickasaw Nation bordered on Blue (Tiger Spring) County in the Choctaw Nation, and that Fisher’s Station in the Choctaw Nation was located only three hundred yards east of the Panola County line. Fisher was a member of both the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations, having been adopted by the Chickasaws by an act of the legislature during the Civil War. Thus, he may have held land in both domains.

Before moving to Tishomingo in 1879 where he operated a “mercantile business on a large scale,” Fisher served in the Civil War in the Choctaw and Chickasaw Regiment under Tandy Walker; ran a store, stage stand and post office in Perryville; was active in politics; and operated a cattle business. Fisher was also a prominent banker in Denison, Texas, and died in Tishomingo in 1898.

Supporting the reliability of Hatchett’s statement that the Fishers acquired the property from the Rider family, the gravestone of Thomas Rider remains on the place. Born in 1814, the date of his death is 1863, so the Rider family may have maintained some connection to the area after selling the place to Fisher. Based on 1860 census records (slave schedule), Thomas Lewis Rider was living in Saline County, Cherokee Nation in 1860, enslaving 11 people. He enlisted as a private at the age of 47 in the Cherokee Mounted Volunteers in 1861. According to civilwaralbum.com, Rider served as a staff mail carrier for Gen. Stand Watie and Gen. Douglas H. Cooper, Confederate States of America (CSA), from 1861 until his death on August 17, 1863. In this capacity, Rider carried mail from CSA headquarters to troops operating in the field, or camped for a time resting and foraging. His son, age 16, replaced him in the field after Rider died and claimed that the “work was dangerous.” For more information see https://www.civilwaralbum.com/indian/rider1.htm

When Roscoe and Margaret Conkling visited Fisher’s Station in 1930, they saw relics of the stage road stretching north and southwest, with several sets of ruts. A building constructed of very old logs remained, probably the last portion of the station then standing. The structure had been improved and added to, but the old section was readily discernible. At the station site they also saw the caved-in well, very old timbers, and foundation stones.

A replica of Fisher’s Station was built for the 1957 Oklahoma Semi-Centennial and displayed at the semi-centennial exposition in Oklahoma City, then moved to Durant for the 1958 celebration of the Butterfield Centennial.

Today, the old well and Rider gravestone are the most discernible remnants of Fisher’s Station, operated not by Fisher Durant nor a Butterfield employee from the east but by a man belonging to both the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations, Osborn Fisher.

For more information on the Butterfield in Indian Territory, see Finding the Butterfield: A Journey Through Time in Indian Territory, available on Amazon at https://a.co/d/aiHX4y4.

Sources:

https://susandragoo.com/butterfield-oklahoma/

Roscoe P. and Margaret B. Conkling, The Butterfield Overland Mail, 1857–1869: Its Organization and Operation over the Southern Route to 1861; Subsequently over the Central Route to 1866; and Under Wells, Fargo and Company in 1869. 3 vols. Glendale, Calif.: Arthur H. Clark, 1947. Vol. 1 of 3, 154.

J.Y. Bryce. “Perryville at One Time Regular Military Post,” Chronicles of Oklahoma 4 no. 2 (Summer 1926).

J.Y. Bryce, “Temporary Markers of Historic Points,” Chronicles of Oklahoma 8, no. 3 (September 1930)

“Carriage Point,” Works Progress Administration Historic Sites and Federal Writers’ Project Collection. Western History Collections. Box 17 Stage Stops and Newspapers, Folder 4.

M. Ruth Hatchett. “Necrology: Isabelle Rebecca Colbert Yarborough.” Chronicles of Oklahoma 37 no. 3 (Autumn 1959).

“Indian Territory is Rich in History,” Durant Daily Democrat, January 28, 1924, 2.

W.B. Morrison. “Colbert Ferry on the Red River, Chickasaw Nation.” Chronicles of Oklahoma 16 no. 3 (September 1938).

“Preston Ferry,” The Vindicator (Atoka, C.N.), July 11, 1872.

Roscoe Conkling Papers. Seaver Center for Western History Research, Los Angeles, Calif.

Muriel Wright to and from R.P. Conkling, October 28, 1935, November 1, 1935, November 7, 1935. Muriel Wright Collection. Box 7, Folder 34.

Muriel H. Wright; Vernon H. Brown, John D. Frizzell, Mildred Frizzell, James D. Morrison, Lucyl A. Shirk, and George H. Shirk. “Committee Report Butterfield Overland Mail.” Chronicles of Oklahoma 36, no. 4 (Winter 1958).

Muriel H. Wright. “Historic Places on the Old Stage Line from Fort Smith to Red River,” Chronicles of Oklahoma 11, no. 2 (June 1933).

Muriel H. Wright. “The Butterfield Overland Mail One Hundred Years Ago.” Chronicles of Oklahoma 35, no. 1 (Spring 1957).

“The End of a Busy Life,” The Daily Ardmoreite, October 24, 1898, 1.